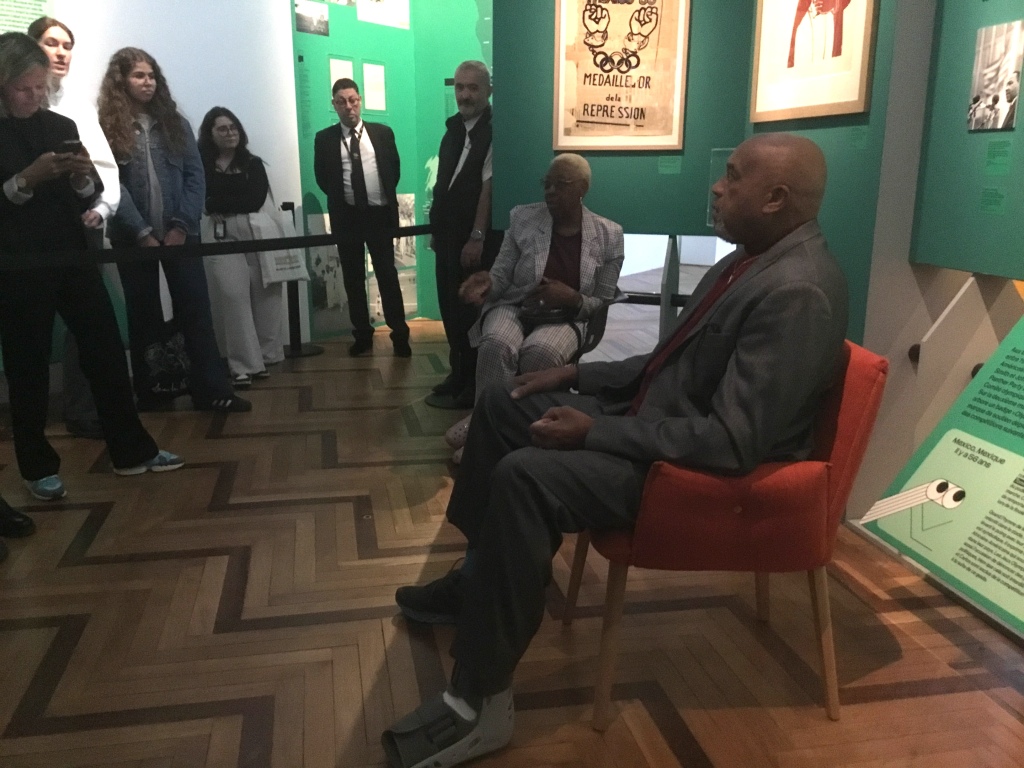

Paris, June 11, 2024, by Socrates George Kazolias

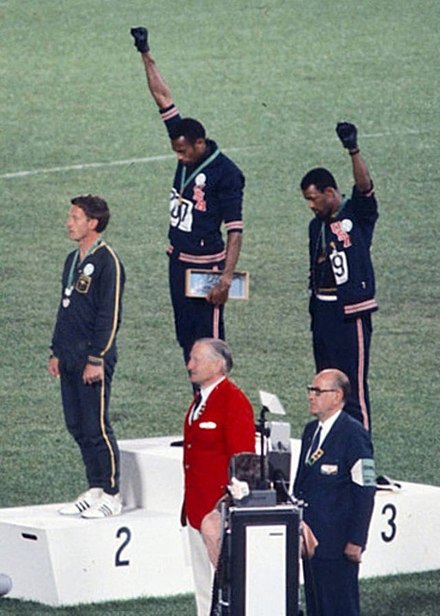

Tommie Smith shocked the world of sports when, after winning the two-hundred-meter Gold Medal in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, he raised a black-gloved fist and bowed his head during the playing of the Star-Spangled Banner to protest discrimination in the United States. Third-placed African American, John Carlos, did the same.

But that display of protest to racism in America almost never happened. John Carlos “forgot to bring his black gloves” even though they had planned it before. So, Tommie gave Carlos his other glove and that is why Tommie has his right gloved fist raised while Carlos his left.

“I question to this day what is the reason for the possibility he forgot his gloves in the first place,” Tommie told reporters of the Anglo-American Press Association on June 11th. “We all have flawed minds, but I feel if you have events such as this, you can’t forget.”

The final decision to raise their fists during the national anthem “was made only ten minutes prior.”

Shortly before the protest, Jesse Owens, the Black athlete who proved to the Nazis at the 1936 Berlin Olympics that you could excel without blond hair and blue eyes, showed up at the Olympic Village to tell Black American athletes there to behave themselves. “Do the best you can and be thankful you are here,” Tommie Smith remembers Owens saying.

Owens “had nothing positive to say about our thoughts or the problems of human rights in our society.” Tommie says Owens was paid by the US Olympic Committee (USOC) to come and do that “because they knew that Tommie Smith was one of these guys who might cause trouble.

“We sat there and listened. We all got up and applauded him. We thanked him and hoped that he would just disappear.”

The head of the International Olympic Committee in 1968 was the American, Avery Brundage, who was head of the USOC in 1936 “and an open racist,” Tommie said. “The man just couldn’t help his attitude. He was a racist from the beginning, period.”

Tommie Smith is now 80 and taught sociology for 35 years. He continues to coach until this day. The theme he keeps coming back to is “teaching kids to do the best you can in whatever you do.”

He said he is proud today that there are hundreds of programs like “Black pride matter. Did I say that right? Black lives matter,” he corrected himself, underscoring he is the product of the 1960’s movement.

He criticizes those who are rich and famous but “don’t do what we think they should do,” to promote human rights because they would rather make money than help people. He encourages youth to “do what you can do to help rather than get rich off of who you are.”

Tommie Smith, who has been invited to the Paris Games, thinks these Olympics “are going to be a lesson. I really do. Like Mexico, 68.”

The fight against racism, discrimination and for inclusivity is at the heart of the Paris Oragnizing Committee’s agenda. But the ‘Olympic Project for Human Rights’ was already two-years old when Tommie and John raised their black-gloved fists nearly 56 years ago.

Tommie Smith points out that it wasn’t easy. His seven sisters and four brothers were insulted, and he was afraid to move around in his small Texas farming town. “Feces and nasty letters were put in the mailbox.” He heard people say he should be killed, that he betrayed his country. “I didn’t betray anybody’s country. It was the truth about the Olympic Project for Human Rights. I had to tell my country.”

When asked if he would do it again, Tommie Smith answered:

“I do it every day. E-V-E-R-Y D-A-Y!”