Tübingen – Baden-Wurtemberg. Most people come to the university town of Tübingen in south-western Germany to admire the colorful medieval and renaissance architecture, walk the ancient cobblestone streets and visit the museum at the castle Schloss Hohentübingen, parts of which date back to the 12th century. Others come for treatment at the world-renowned university hospitals. But this summer, the city’s Green Party lord-mayor, Boris Palmer, inaugurated another kind of visit aimed at a German public: the city’s Nazi past.

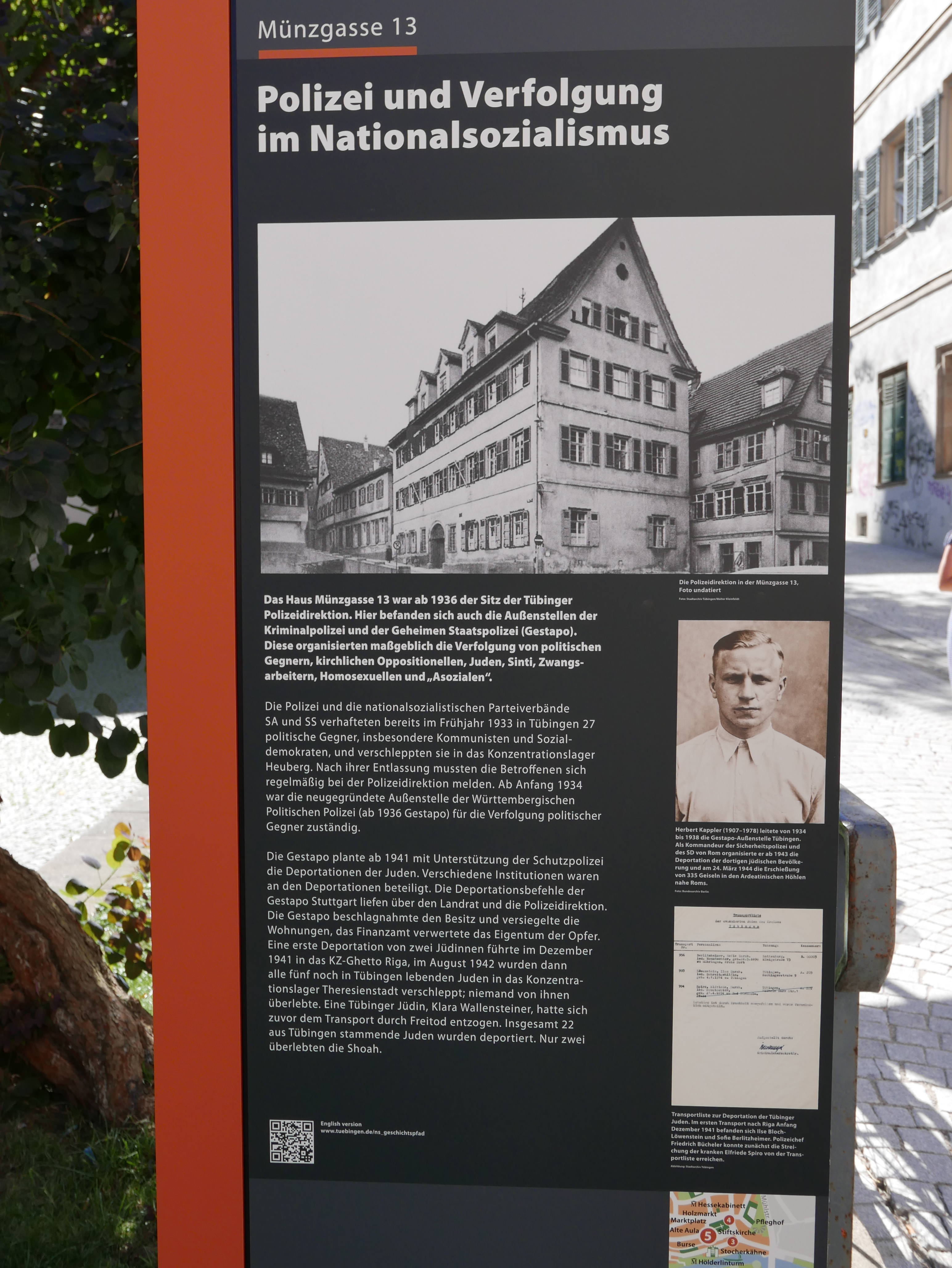

Sixteen historical makers spread out around the city along the ‘Tübingen History Path to National Socialism’ tell the story of the victims and the perpetrators who lived here during the Third Reich. The texts, created with the help of Tübingen’s university working group which researches and documents Nazi crimes, the Arbeitskreis zum Nationalsozialismus and the Tübingen History Club, are only in German but you can find English translations online by scanning the QR Codes on the panels. A free map of the Holocaust Trail is available at the Tourist Office on the right side of the bridge over the Neckar River.

The tour begins at the Synagogenplatz monument located at a lot on Gartenstrasse where Tübingen’s Jews worshipped until their Synagogue was burned down on Kristalnacht, November 9, 1938. The historical marker tells us the Temple, built in 1882, began suffering vandalism in 1928 when anti-semites threw stones through the windows. Here you will find the Tübingen Synagogue Memorial erected in 2000.

A iron cube honors the Synagogue itself. The 101 holes in it represent the Jewish who lived in the city in 1933 when the Nazis came to power. Their names are carved through three large plaques over a narrow water canal. A cornerstone from the Synagogue can be seen in the car garage at Gartenstrasse 33 and to the left of the apartment building are remnants of the Synagogue’s entrance.

The historical marker tells us that some 80 of the city’s Jews had sold everything they owned and emigrated to other countries by 1940. Twenty-three others were deported to concentration camps in 1941 & 42. The names of the only two to survive are at the bottom of the third plaque: in 1945 one survivor went to Palestine while the other emigrated to New York.

It probably did not help that the headquarters of the Hitler Youth was less than a hundred yards up the street from the Synagogue at Gartenstrasse 22. But anti-semitism was already rampant among the city’s student-body in the 1920s when the Fraternities enacted the “Arierparagraphen”, the Aryan Paragraph, banning Jewish students from joining or participating in any activities. Fraternity members were known for insulting Jews and even aggressing them in the streets as early as 1921.

1. RIDER WITH HORSE, BRONZE STATUE BY FRITZ VON GRAEVENITZ -1936. NAZI ART.

2. THE NAZI YOUTH CENTER IS NOW A 141-BED STUDENT HOSTEL

The NAZI Past is Ever Present

The Hitler Youth headquarters was built in 1934 with ‘educating’ the teenage Aryans as its purpose, The large, three-story, building today is a 141-bed youth hostel where young people from around the world linger after a long day of visits. From the cafeteria you can watch the punting boats being gently pushed along the water. The visitors don’t know that this was once a hot bed of Nazi activity aimed at their age group. Next to the hostel’s peaceful terrace, with a splendid view over the Neckar River, is the bronze statue by Fritz von Graevenitz: Rider with Horse. The statue was ordered in 1936 and inaugurated in 1938. It satisfied all the requirements of Nazi art which you learn more about at historical marker number 12.

Just opposite Tübingen’s left leaning daily newspaper, the Schwäbisches Tagblatt, on Uhlandstrasse 2, is the story of Jewish publisher Albert Weil who moved to the city in 1903 and bought the Tübinger Chronik paper. It is also where Weil and his family of eight lived. Albert turned the Chronik around, investing in modern equipment and made the paper a large circulation daily but was vilified from the Nazi run Tübingen Zeitung and harassed by Fraternity students. In 1930, Albert sold the paper and he and his wife emigrated to Switzerland but he placed his son, Hermann, as managing editor with a ten-year contract. The Nazis would see to that in 1933. Hermann fled with his family to farm in what is today Tanzania. The Schwäbisches Tagblatt runs the name Tübinger Chronik in blue under its own banner.

Half-way across the Neckar bridge you take the stairs down to Plantanenallee on the island in the river. At the end of the long row of Plane trees is the Silcher Memorial where historical marker number 12 tells you how the Nazis appropriated the Arts for their ends. The statue to the 19th century folk song composer, Friedrich Silcher, by Stuttgart sculpture Wilhelm Julius Frick is National Socialist art at its best. The composer sits facing front and two soldiers and a boy with a rifle are on the back.

Citizens of Tübingen repeatedly called for the Nazi statue to be removed following the war. As a compromise the state of Baden-Wurttemberg added the date “1941” to its pedestal. Silcher holds a special place in German hearts as the father of the “Sangesbewegung” singing movement. Folk choirs inspired by the movement continue to this day.

But what of a university town under Nazi rule? At the castle, which was used by professors for research including the Institute for German Ethnology and the Institute for Racial Studies, you learn that intellectuals were giving the Nazis the kind of scientific “proof” they needed. They also played an active role in the horror. Racial Studies faculty member Hans Fleischhacker handpicked 86 Jewish inmates at Auschwitz so they could be murdered because the Riech University of Strasbourg needed skeletons for their collection. Professor Fleischhacker, whose 1943 thesis said that “the Jewish race could be proved through hand prints”, died in 1992. He was 80.

But Tübingen is also a university hospital city. From the castle you can see on the mountain on the other side of town the Psychiatric hospital which was in charge of naming candidates for forced sterilization; basically people the Nazis thought should not be allowed to transfer their genes. Between 1934 and 1944, over 1,100 men, women and children who were declared “erbkrank” (hereditarily diseased) were sterilized at the gynecological and surgical hospitals. Gynecologist August Mayer, under whose direction 655 women were forcibly sterilized and who remained director of the hospital until 1949, died in 1968. He was 92.

Medical students dissected the bodies of over 500 Nazi victims and buried them in a potter’s field called “Plot X.”. The Anatomical Institute at the university got rid of the last specimens in its collection from the Nazi era in 1989.

The story of Tübingen in the Third Reich shows the Nazi movement did not just rely on the fists of under-educated ‘losers’. To quote the working group: “a majority of the students and professors, parts of the middle class as well as a number of public officials were harboring nationalist, anti-democratic, and anti-semitic sentiments.”

Historical marker number 3 is titled “Perpetrators of the Holocaust” and tells the story of Theodor Dannecker who, as Adolf Eichmann’s Jewish affairs advisor, was responsible for the deportation of 476,000 Jews from several countries. Dannecker’s parents owned a clothing store across the street from the marker at Bursagassse 18 which he was destined to take over. Dannecker committed suicide while in American detention in 1945.

SS headquarters are in front of the entrance to Saint George Church. On the Marktplatz, in front of City Hall, you can see photos of crowds giving the Hitler salute the day the municipal council was disbanded, the building decked in the Nazi flag. Elsewhere around town, bronze plates among the cobblestones in front of a house tell the names of Jews who once lived there. The caserne where the Wehrmacht was headquartered is on the other side of the train station. Historical marker number 16 at a second train station is a bit out of town and tells the story of Russian prisoners of war and East European forced labor prisoners brought to Tübingen.

There is also the Oppenheim and Schäfer clothing store. A photo shows brown-shirt stormtroopers in 1933 preventing people from shopping there before the shop was forcibly “Aryanized” like other Jewish businesses in 1938. Jews were expropriated and forced to sell at ridiculously low prices in what was a government imposed “buyers market.”

Löwen Hall, marker number 8, where leftists and labor met, reminds us of what happens when you organize for resistance too late. Many of the leftist activists ended up in camps while others simply joined the ranks. One resister was a printer at the Tübinger Chronik who resigned when the Nazis took it over in 1933: Heinrich Kost. He saved precious documents the university working groups have been able to put to good use.

Tübingen’s History Path to National Socialism comes at a time when right-wing populism, anti-semitism and racism are on the rise and when many of Germany’s youth say they are fed up with hearing about what their Great-Grandfathers did. It comes at a time when Chancellor Angela Merkel’s open door policy to Muslim immigrants has provoked deep fears and rejection, not all that different from what the historical markers show happened before 1933.

All Photos by c.KAZOLIAS.COM: The brass plates (1) for the Oppenheim family in front of where their clothing shop and home. The shop was ransacked by the NAZIs during Kristallnacht, Nov. 9-10, 1938, and (2) the building today which is still a clothing store. Across the street (3) is the historical marker where you can see an image of the building when the Oppenheim owned it. They feld Germany for the USA after Kristallnacht.